The lifespan of a goalkeeper means their ‘peak years’ come later. What role does age play in their development?

The lifespan of a goalkeeper is typically longer than that of an outfield player. Whilst most footballers hang up their boots around their mid-30s, a decent proportion of those entrusted between the sticks continue to don their gloves into their late-30s – and well beyond.

Indeed, there are numerous examples of goalkeepers who successfully navigate beyond the 40-year-old threshold. Italian icon Gianluigi Buffon, who incidentally was last season supported by a coach nine years his junior at Serie B outfit Parma, is now 45 years of age, whilst Neville Southall, a cult hero at Goodison Park following his remarkable period on Merseyside, retired at 43, a colossal 28 years after signing for first club Llandudno Town.

Furthermore, goalkeepers still compete at the highest level until a more advanced stage in their career, with many featuring in elite competition even as they approach the twilight of their playing days. Legendary shot-stopper John Burridge, who turned out for no fewer than 26 clubs at various levels of the English footballing pyramid, still retains the record for being the oldest-ever Premier League player, featuring for Manchester City on the last day of the 1994/95 campaign at the modest age of 43 years, 5 months, and 11 days.

Moreover, nine of the league’s top ten oldest competitors have been goalkeepers; Teddy Sheringham is the only outfielder to appear in this illustrious list, whilst Ryan Giggs is just edged out by former Manchester United teammate Edwin Van der Sar.

Clearly, with significantly less ground to cover and fewer prolonged moments of intense exertion, goalkeepers assume a different physical role to their outfield colleagues, providing one reason as to their increased lifespan. A study by the Athletic attested to this, proving the greater longevity of goalkeepers.

Nevertheless, this does not necessarily explain two universally-held viewpoints: goalkeepers arrive at their peak later than outfield players, and maintain a more consistent standard of performance towards the end of their careers. Are these prevailing narratives are in fact true? And, if they are proven to be accurate, what explains them?

*

Although the old adage, ‘goalkeepers get better with age’ is perhaps too loose a description to depict their development journey, most would attest to the view that a goalkeeper’s progression towards veteran status is something that should be embraced rather than feared. True, as Greek journeyman Dimi Konstantopoulos revealed in an interview with Goalkeeper.com last July, even at 34 years of age when the former Middlesbrough stopper reached the Premier League with the Teesside club, he felt far more than a ‘spare pair of gloves’.

Of course, the de-prioritization of physical attributes lends itself well to those aiming to extend their playing careers, but a key catalyst for continued participation is the nature of a goalkeeper’s required cognitive skills, which are generally sharpened through practice and experience.

The ability to make rational and timely decisions in ambiguous circumstances, a quality all decent goalkeepers possess, naturally develops with maturity. Organizational skills on the pitch, deployed regularly to help mobilise defensive lines, strategically position markers at set-pieces, and compartmentalize the shooting habits of opposition players, also tend to improve immeasurably with repetition and increased familiarity with different playing styles, teammate personalities, and scenarios.

Furthermore, a goalkeeper’s communicative style, often used as a partial barometer towards judging overall capability, is always in a state of continuous development. Messages become ever-more confidently and succinctly delivered – not to mention with increasing authority and assertiveness. The respect teammates have for a tried and tested goalkeeper will enhance their natural leadership qualification.

Clearly, goalkeepers are not exempt from undertaking physically taxing activities, but these generally test abilities which take much longer to erode than those associated with outfield endeavours. In very simplistic terms, a goalkeeper’s proclivity for saving shots and handling cross-balls are not things in themselves overtly influenced by age, although agility, flexibility, and dexterity is admittedly impacted over time.

However, given the recent evolution of goalkeeping, whereby those in nets are expected to perform as competently with their feet as they are with their hands, there is some doubt as to whether this trend will continue – or at least exist to the same degree.

Goalkeepers are expected to deliver everything they have always been asked to do, but also now operate as an auxiliary sweeper, suffocating any danger from long balls clipped over defences, and effectively becoming an eleventh outfield player in possession.

Whilst the goalkeeping population has risen admirably to the challenge since the inception of this new playing philosophy, the impact this could have on career durability is perhaps yet to materialise. Will aging goalkeepers be able to withstand the pressures of their recently revised role?

*

The rapid hyper-professionalisation of the sport in the last two decades, where nutritional specialists, fitness gurus, and mindset experts contribute significantly to the back-of-house operation, ensures players retain match sharpness for a greater period of time. Therefore, we are now unable to draw like-for-like retirement age comparisons when reflecting on previous eras; modern-day goalkeepers, just like outfielders, will inevitably play for longer. Nevertheless, the bandwidth in career length between these two sets of players may tighten in the future.

However, have the coaching methodologies which accompany this re-calibration of duties expedited the learning process, and therefore impacted when goalkeepers reach the height of their capabilities?

Previously, goalkeepers trained in almost permanent isolation, siphoned away from the rest of the playing squad for hours, before perhaps re-uniting with teammates for a quick practice game at a session’s conclusion. Ex-MLS goalkeeper Justin Bryant commented on how “goalkeeper coaching became more common later in the 1980s. I think the biggest difference between then and now is that now we try to make coaching much more game-realistic, whereas back then, the idea was training goalkeepers in a very high-volume, high-intensity workload. Lots of drills were designed to work the goalkeeper into exhaustion”.

However, goalkeepers are now far more integrated into general squad drills than ever before, a natural by-product of their elevated contribution to the team formulating its desired playing style. As a direct result, goalkeepers are more regularly exposed to activities which serve to simulate matchday situations; positional work is undertaken with fellow defensive colleagues in situ, incoming shots are delivered by attacking players rather than goalkeeping coaches, and handling exercises take place in crowded rather than empty penalty boxes.

Of course, given the stark contrast in required skill sets between goalkeepers and outfield players, periods of independent training are still necessary, but a healthier balance has undoubtedly been struck.

As we have already surmised, the trajectory of a goalkeeper’s development is often index-linked to their level of ‘real-world’ experience. Therefore, replicating in-game conditions during training is surely hugely advantageous for youngsters eager to supercharge their progression. Indeed, a cursory glance at the statistics would suggest the changing dynamics of goalkeeping responsibilities – and by extension the adoption of new training techniques – has pre-empted a recessive movement in the age players in this position hit their ‘peak’.

The consensus has always been that goalkeepers enjoy their richest vein of form in their early 30s, several years after outfielders typically play their best football. However, with every passing season, this notion feels increasingly outdated. If we look at the current variety of Premier League number ones, we see fourteen of the 34 goalkeepers to make an appearance this season under the age of thirty. Of the fifteen to have made more than 25 appearances, seven are below this threshold. And, between those who have played the maximum possible number of games so far this season (31), the average age is actually 25.

The average age of this season's Premier League goalkeepers with an appearance so far is around 29. Last season (2021/2022), it was almost identical, at 29.07 years. The year before, it was younger, at 27.4 years. The year before, once again around 29. So, between 27 and 29 has, since the 2019/20 season, been the average goalkeeper age. Whether this equates to a ‘prime’ age is debatable.

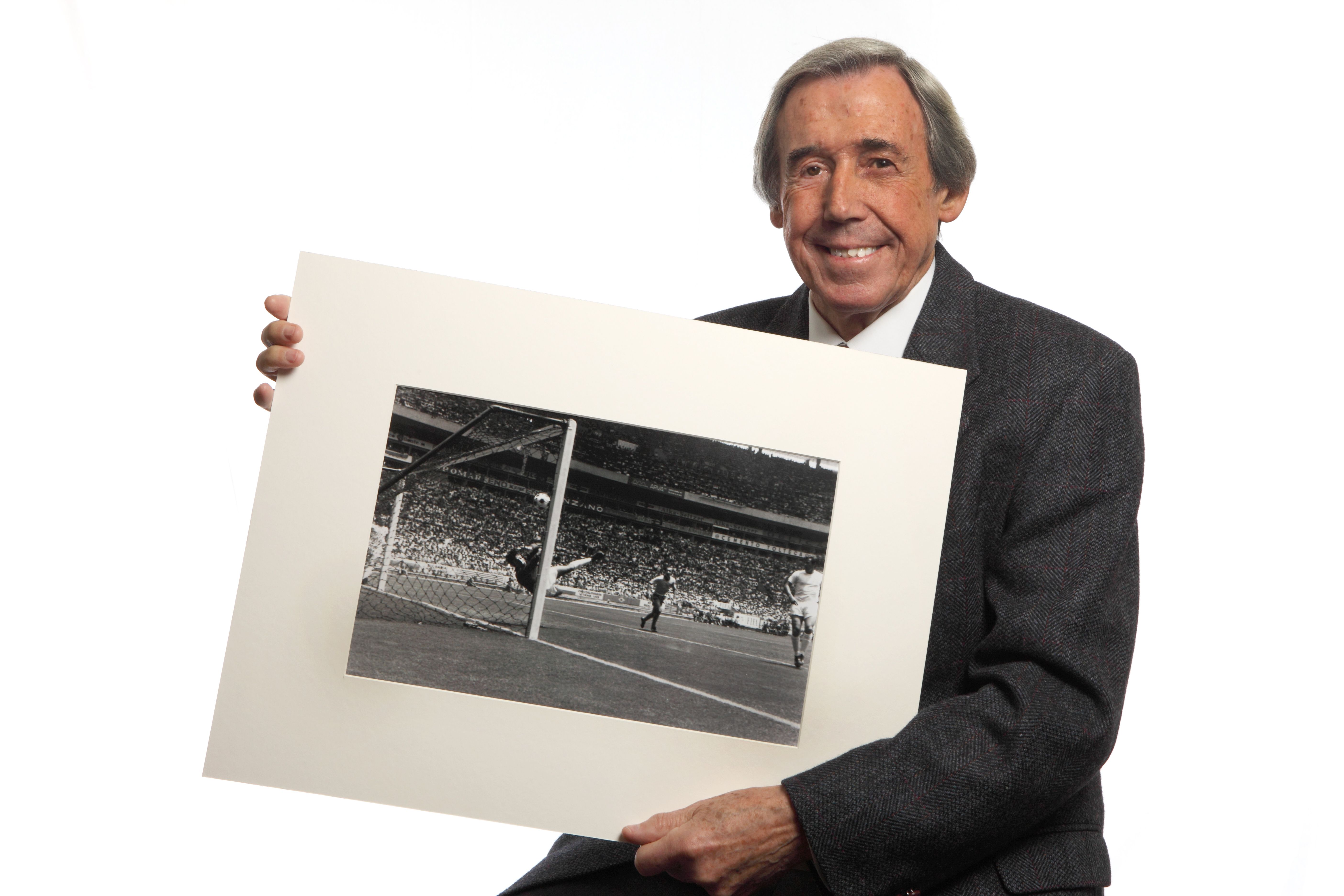

This reality is not restricted to England’s domestic theatre, with its international team also subject to a similar age re-configuration within its goalkeeping department in recent times. In World Cup matches between 1970 and 2010, inclusive of fixtures which took place in Mexico and South Africa at extreme ends of this 44-year timeframe, the average age of goalkeepers fielded by England was 34. In the three tournaments since 2014, with Messrs Hart and Pickford picking up the mantle, the equivalent figure reduces by eight years.

With Jordan Pickford still first-choice and a 24-year-old Aaron Ramsdale waiting patiently in the wings, the days where an ageing Banks, Shilton or Seaman would have been routinely called upon now seem like a distant memory.

So, is there a direct correlation between the age of a goalkeeper and the scope of their capability? Even in a contemporary context, the answer to this question must be yes.

Whilst some commentators will attempt to portray the current goalkeeping crop as a completely different breed to their predecessors, it would be naïve to suggest the core functions of their discipline have fundamentally changed. Given a goalkeeper’s privileged view of on-field action, alongside, of course, shot-stopping (the primary aim of the position), being able to effectively communicate, make well-informed decisions, and appropriately delegate defensive responsibilities will always be essential.

These assets are cultivated through experience, and therefore, in this regard at least, goalkeepers become better versions of themselves as their careers progress – even into the latter stages. Nevertheless, the expectations now leveraged on goalkeepers, whereby greater mobility and a heightened involvement in build-up play is demanded, could lead to the gap in retirement age between goalkeepers and outfield players constricting in years to come.

Whatever happens, it is unlikely that a goalkeeper’s age will ever influence recruitment and matchday selection strategies in the same way that it does for outfield players. In this way, the ‘purity’ of the position feels better protected; there is no inherent bias that performance will gradually deteriorate over time. In this way, the phrase ‘if you’re good enough, you’re old enough’ can be caveated by saying ‘if you’re older, the chances are you’re still good enough’. Interestingly, both statements still have relevance in the context of today’s game.

And in, the case of Gianluigi Buffon - who has arguably straddled two generations, with each championing very different attitudes towards the role of a goalkeeper – let’s see how long he has left in the tank.