Astronomer and goalkeeping analyst Dr. John Harrison presents the case for the importance of measuring ‘shot-prevention’, and whether this is more important than making saves themselves…

It is often said that the main aim of a goalkeeper has always been, and will always be, to stop shots from going into the net. Even in the modern game, where there is a greater emphasis on a goalkeeper's distribution and sweeping skills, shot-stopping is still accepted as the most important skill a goalkeeper needs to master.

But although shot-stopping forms the basis of any goalkeeper’s job description, there’s certainly more to stopping goals occurring than just that. This is where ‘shot-preventing’ - a very misunderstood statistic in goalkeeping data - comes into play.

Every on-pitch action a goalkeeper performs can be placed into one of three categories: shot- stopping, shot-preventing, or distributing. The first two of these are defensive, and actively ‘stop goals’. For goalkeeping analysts and scouts, knowing the relative importance of shot-stopping and shot-preventing will allow goalkeepers with vastly different strengths and skill sets to be more fairly compared and evaluated.

For goalkeepers and goalkeeper coaches, understanding the relative importance of each of these three aspects of goalkeeping to on-pitch performance is vital. We can even use the relative importance of each set of statistics to go as far as to know how to plan training sessions by timings.

But what actually is ‘shot-preventing’? How far can we go with mainstream statistics? And, which goalkeepers are good examples of the positive and negative effects of this statistically misunderstood skill?

What metrics can we use to evaluate shot prevention?

While a shot stopping action is an action which actually stops the ball from crossing the goal line, a shot preventing action is an action which prevents a shot from ever happening in the first place.

If we want to analyse the importance of shot-prevention, we must move way beyond mainstream publicly available metrics. The first major issue with the available data regarding shot prevention is that many shot preventing actions are not counted by mainstream statistic providers.

Most statistic providers split what goalkeepers and goalkeeper coaches would call shot-preventing actions into recoveries, tackles, interceptions, punches, high claims (cross claims), and sweeps. The problem with this is that many shot-preventing actions do not fall cleanly into any of those categories and some fall into multiple categories. Hence, some shot-preventing actions do not get measured while others can get measured multiple times. Additionally, the difference between the categories is unclear and not in any way related to difficulty or importance.

Here is an example of this issue in action in a Premier League match. Both Opta and StatsBomb reported three shot-preventing action categories for Manchester United’s David De Gea in their match against Norwich City at Carrow Road earlier this season:

- Sweeps

- Punches

- Cross claims

Both Opta and Statsbomb suggested that De Gea made no sweeps, no punches, and one cross claim against Norwich. However, if you watch the full match footage you will find these four shot preventing actions occurred:

It is unclear as to why three of these four actions were missed but from the images above we can see that all four actions were shot-preventing actions and therefore were worth logging. It’s important to note that this is not a one-off occurrence. When compiling my database of shot-preventing actions over the past few years, I found that nearly all Premier League games had multiple missing shot-preventing actions. This, simply put, is the major reason that publicly available data cannot be used to assess shot-preventing.

The second reason that publicly available data cannot be used to assess the importance of shot-preventing is that even if the public data was complete, it would still not inform us as to whether the action actually prevented a potential shot from occurring. The images below outline an example highlighting why not all actions should be evaluated in the same manner:

The claim on the left stops the ball from sailing out for a goal kick, while the claim on the right stops John Stones having a free header on goal. It is crucial to know if a potential scoring opportunity is prevented when a claim or sweep occurs if the aim is, to assess how useful shot-prevention skills are when it comes to helping a team concede fewer goals.

The third reason that publicly available data cannot be used to assess the importance of shot-preventing is that, even if we ignore the other two previously outlined issues, such basic data also gives us no indication of how often each individual cross or through ball would be dealt with by a Premier League goalkeeper. Similarly, it doesn’t alone explain how often a goal would occur after a given individual cross or through ball in the Premier League if the goalkeeper did not intervene. The images below outline an example highlighting why not all shot preventing actions are of equal difficulty or worth to the defending team.

To assess how useful shot-prevention skills are when it comes to helping a team concede fewer goals, we must find a way of:

- Estimating how difficult a shot-preventing action is to make, quantitatively

- How likely it is a goal will occur if the action was not successfully made

This will allow us to estimate the number of extra goals conceded that would likely occur if a team went from having an excellent shot preventer between the sticks to having a woeful one.

The final issue with publicly available data is that it fails to measure how well the goalkeeper deals with the cross or through ball when they do intervene. The images below outline an example highlighting why not all interventions by goalkeepers are of equal quality and thus do not decrease the chance of a goal being scored by the same magnitude.

So, we now know that a useful shot preventing metric/model must take into account:

- All potentially shot-preventing actions

- If an action actually prevents a potential shot

- The quality of the potential shot that the action prevents

- The difficulty of the action

- The quality of the intervention in terms of how it affects the probability of a goal occurring

In the case of De Gea and Alisson, how important is shot-preventing compared to shot-stopping?

I chose to highlight these goalkeepers as they are representative of the difference between the best shot preventers and the worst shot preventers in the Premier League over the past few seasons.

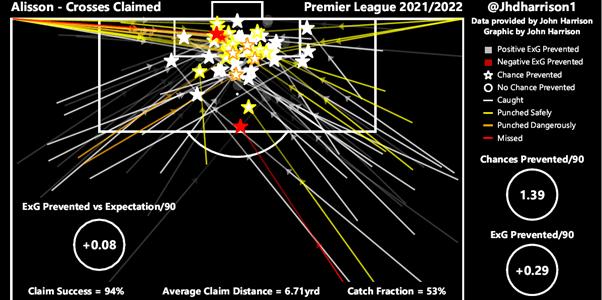

Alisson is a very active goalkeeper when it comes to claiming crosses. In the 21/22 season, he ‘prevented’ (not ‘stopped’) 0.29 expected goals due to claiming crosses per 90 minutes for Liverpool. When this is compared with the number of expected goals an average Premier League goalkeeper would be expected to prevent given the crosses Alisson has faced, the model suggests that Alisson has prevented an additional 0.08 expected goals per 90 minutes.

That means Liverpool would concede one additional goal worth of chances from crosses every 12 games if they had an ‘average’ Premier League goalkeeper in goal rather than Alisson.

De Gea, on the other hand, is a far less active goalkeeper when it comes to claiming crosses De Gea has played 180 more minutes of Premier League football in this sample. However, his graphic has far fewer interventions on it, and they are far closer to his goal line. According to my model, De Gea has prevented 0.17 expected goals per 90 minutes for Manchester United

When this is compared with the number of expected goals an average Premier League goalkeeper would be expected to prevent given the crosses De Gea has faced, the model suggests that De Gea has actually allowed Manchester United to concede an additional 0.12 expected goals per 90 minutes.

When it comes to sweeping, the story is pretty much the same. Alisson is a very active sweeper and according to my model, he has prevented 0.22 expected goals per 90 minutes for Liverpool. When this is compared with the number of expected goals an average Premier League goalkeeper would be expected to prevent given the through balls Alisson has faced, the model suggests that Alisson has prevented an additional 0.07 expected goals per 90 minutes.

Interestingly, from the graphic below, we can see that Alisson isn’t perfect when he sweeps. In fact, he has increased the probability of a goal being scored on two occasions. Yet, his frequency of sweeping actions means that the good outweighs the bad and he helps facilitate their high defensive line.

Again, De Gea is a far less active goalkeeper. Bearing in mind the Spaniard has played an additional 180 minutes, the graphics again show a stark difference in sweeping activity. De Gea does have a perfect sweeping record in the sense that, when he has intervened, he has always reduced the probability of the sequence becoming a goal, however, United’s number one intervenes so infrequently that his sweeping is far less useful to Manchester United than Alisson is to Liverpool.

According to my model, De Gea has only prevented 0.09 expected goals per 90 minutes for Manchester United by sweeping. When this is compared with the number of expected goals an average Premier League goalkeeper would be expected to prevent given the through balls De Gea has faced, the model suggests that De Gea has actually allowed Manchester United to concede an additional 0.04 expected goals per 90 minutes.

Overall, the data shows that Alisson is clearly a very proactive goalkeeper while De Gea is much more of a ‘line goalkeeper’. In the 21/22 Premier League season, Alisson has prevented Liverpool conceding an additional 0.15 expected goals per game (ExG) while De Gea has allowed Manchester United to concede an additional 0.16 expected goals per game.

This difference (between an above average and below average shot-preventer) results in around a 0.3 ExG per game which can now be directly compared to the difference between having a top-class Premier League shot stopper and a poor Premier League shot stopper. Therefore, the relative importance of shot-prevention can be evaluated.

The difference in shot-stopping from the current market leading post-shot expected goals models turns out to be roughly 0.6 ExG per game which means that shot-prevention is roughly half as important as shot stopping.

So, the old sayings are not wrong: shot stopping is still the most important skill a goalkeeper can have. However, its importance is not so great that shot-preventing can be ignored. ‘Line goalkeepers’ like David De Gea have to be truly exceptional shot-stoppers if they wish to be worth as much to their team as the current crop of all-round modern-day goalkeepers.

Finally, given expected goals suggests shot-prevention is half as important as shot stopping (at 0.3ExG), shot-prevention skills warrant approximately a third of a goalkeeper’s time on the training ground, and approximately a third of a goalkeeping scout’s assessment, should be dedicated to shot prevention in that context.

Keep up to date with The Astronomer Goalkeeper on Twitter, @jhdharrison1, powered by Goalkeeper.com.