This Remembrance Sunday stirs memories of two Welsh goalkeepers who served in the two World Wars. They died over 100 years apart, but their fate had striking similarities…

Although an FA panel found Crystal Palace’s Wayne Hennessey not guilty of knowingly making a Nazi salute during a team bonding meal in 2019, their written missive sent a powerful message. The report stated: “All we would say (at the risk of sounding patronising) is that Mr Hennessey would be well advised to familiarise himself with events which continue to have great significance to those who live in a free country.”+

Hennessey would have been well advised to make the short trek to South West London just a few months later to learn about Europe’s darkest hours. A fellow Welsh goalkeeper's tale was waiting there.

The anti-Semitism mural unveiled at Stamford Bridge in January 2020 commemorated Holocaust Remembrance Day with a 12-metre art installation depicting three players sent to Nazi death camps. One of them was Ron Jones, a Welsh prisoner of war known as the ‘Goalkeeper of Auschwitz’.

The lifelong Newport County fan, who died in September 2019 at the age of 102, was originally exempt from conscription. He was a key skilled worker at a factory in Cardiff turning metal into wire, a crucial skill for the war effort. However, a typist accidentally put the paperwork in the wrong pile to change the course of his life.

Jones joined the 1st Battalion of the Welch Regiment and was captured in Libya by the Germans in 1942. Eventually, he was transferred to camp E715, where British Prisoners of War were held alongside the Nazis’ main extermination base in Poland.

The realisation there was something far worse than the odour of the hazardous chemicals of the factory dawned on him: “If the wind was in your direction the smell was terrible. It was the burning flesh from bodies being burned. We were always frightened we would be next".

The fear could wait for a couple of hours on a Sunday. The captured PoWs were allowed leisure time on the field located next to the horrors of Birkenau. The ‘privileged’ British footballers would play with a rag ball and some creative use of material resources in terms of boots, posts, and pitch. Germans watched on with their rifles.

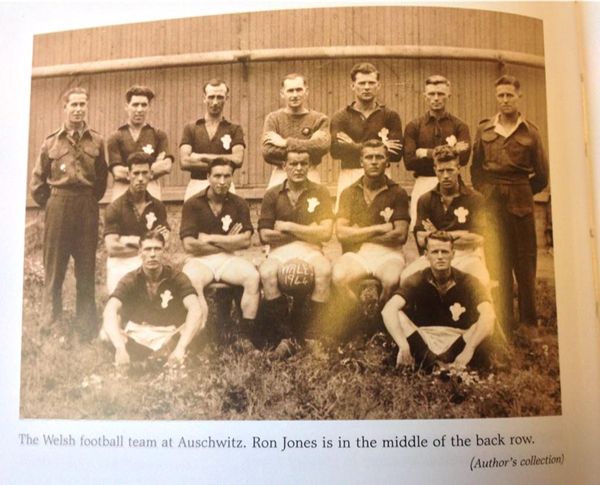

Cigarettes were used as a trade between prisoners and guards alike to try and gain better equipment until, on one of their rare inspections, the International Red Cross sent them four loads of shirts – English, Scottish, Irish and Welsh as an unofficial Home Nations team became a reality. Jones was the goalkeeper for the Dragons.

Utilising skills learnt from his mother, Jones sewed a Prince of Wales feather emblem to each of his player’s socks. This was a tournament like no other, a green shoot of life in the shadow of death. It contributed to survival in more ways than one.

The former lance corporal remembers: “You could say the football we played saved our lives. The football lads were fitter, yes, but more than that, they belonged to a group which kept each other going on the march." That ‘march’ was fatal for many soldiers as the Nazis moved the prisoners on a trek through Europe when they learned that Russian forces were en route to free the camp.

For more than four months, almost 250 men walked for 900 miles through the Carpathian Mountains, Czechoslovakia, Saxony, and Bavaria, eventually reaching Regensburg in Austria. Many froze or starved as they lived on nothing more than animal scraps in the barns they were kept in before being liberated by the Americans in 1945.

Jones baulked at other POW accounts citing heroic aspects to this story as some boys’ own adventure. Britain’s oldest poppy seller never forgot the horrors of what went on within the walls of the Third Reich, seen or unseen.

For another goalkeeper-oriented example of courage in the face of overwhelming odds, the dial goes back to the Great War. Welshman Leigh Roose played for Stoke, Aston Villa, Sunderland and Arsenal, as well as being a key player when Wales won their first British Home Championships in 1907. As with Auschwitz’s unofficial wartime tournament in 1944, Roose’s 24 international caps were earnt against Scotland, Ireland and England.

He was awarded the Military Medal after his very first skirmish. The regimental records described his actions in the flamethrower attack at Ration Trench near Pozières in August 1916: “He (Roose) managed to get back along the trench and, though nearly choked with fumes with his clothes burnt, refused to go to the dressing station. He continued to throw bombs until his arm gave out, and then, joining the covering party, used his rifle with great effect.”

Perhaps part of his fearlessness came from the roughhouse of the then-First Division. A high pain threshold was a trait that was a prerequisite for unprotected goalkeepers in the early 20th century. They could handle the ball basketball-style anywhere inside their half but most didn’t venture out for fear of suffering the common rugby-style attacks from other players.

The Wrexham-born man was one of the few that had the temerity to go forth. His outfield adventures rubbed up the authorities the wrong way and ultimately led to a rule change in 1912 which meant custodians could only handle inside the area.

He was voted among the ten most recognisable faces in London and went out with a music hall star to bring an element of 20th century celebrity style off the pitch. On the field, he used to sit on top of the crossbar when play was down at the other end, performing spontaneous gymnastic routines. There was simply no way to contain the personality or physicality of the 6"1 ft, 13 stone ‘Hercules’. Roose’s goalkeeping skills were not in question either.

“He was a pioneer, self-taught, relying on his instinct to learn and get things right”, says Neville Southall, who regards the former Everton stopper as one of his heroes. Forget Lev Yashin. It was a Welshman who truly changed the role of the goalkeeper from reactionary to a more active role, and in his own words, to “build the foundations for swift, incisive counter-attacking play".

Typically, he met his fate head-on, hurtling towards a heavily armed German unit at the village of Gueudecourt in October 1916 during the Battle of the Somme. 2nd Lt Gordon Hoare, who scored two goals in Great Britain’s 1912 Olympics final win over Hungary, witnessed the 38-year-old running at great speed across no man’s land towards the entrenched German machine guns, firing his rifle. His body was never found.

How ironic that another administrative error closes the story, bringing a poignant connection between these two Welsh greats who wore the national jersey with pride. When he joined up with the Royal Fusiliers, a recruitment officer spelt Roose “Rouse”, a slip that caused great uncertainty to his family as they searched for news. The War Office confirmed that of the four soldiers killed between 1914 and 1918 with the surname Roose, none had been christened Leigh.

It was only a long-standing campaign from family and friends that led to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission finally sending a stone mason to correct the error in December 2016, a century after he ran towards those machine guns. L Roose finally took its place next to the inscriptions of 72000 missing British and South African troops at the Thiepval memorial.

As another Remembrance weekend passes across Premier League grounds, respect will be paid to the veterans and those that made the ultimate sacrifice. The goalkeepers who fell to the ground for the last time will not be forgotten.