Leeds’ goalkeeping guru gives an insight into working in an array of different environments across the divisions…

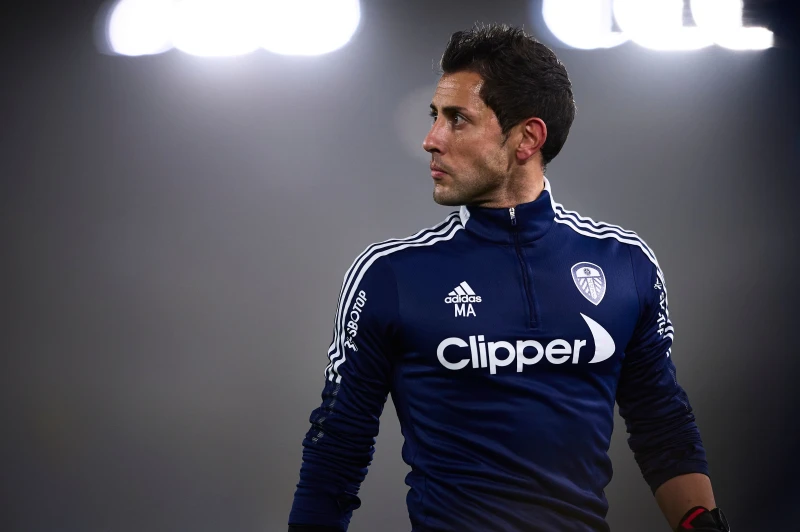

When Spanish goalkeeping coach Marcos Abad arrived in Middlesbrough in February 2017 for his first taste of English football, he had to adapt. Not only was the language spoken different, but so was the language of football - and especially the language of goalkeeping.

Only 32 at the time, Abad was stepping into a new country, and a new footballing culture. Brought to Middlesbrough by then-Boro Director of Football Victor Orta (who had worked with Abad at Elche) to work alongside Aitor Karanka, the Spaniard was tasked with revitalising a highly experienced goalkeeping department of Victor Valdes, Brad Guzan, and Dimi Konstantopoulos.

“It was a really, really quick decision. A dream of mine - as with many in Spain - is to get experience in English football. Working here is so different in many ways, compared to other countries - the fans, for example”, says Abad.

“I’ll be honest, even when I was a child I knew that a life experience I wanted to have was to live in England, even if it was just working in a hotel! So to have the opportunity to do it in football left me with no doubts to go. It was my challenge - my opportunity”.

At the time of Abad’s arrival, Boro sat 15th in the Premier League table. The Teeside club were three places clear of the relegation zone, but the point-based reality was more precarious; Middlesbrough were only a point clear of Hull City in 18th. Seven games into a to-be 16 match winless run at the time (boss Aitor Karanka would lose his job when that sequence hit ten), Valdes was holding onto the number one shirt. The Spaniard would play 28 Premier League matches that season, with Guzan filling in for the remaining ten.

Teesside legend Dimi Konstantopoulos, meanwhile, who had greatly aided Middlesbrough’s promotion cause and set a new club record of 22 clean sheets that season, was never granted the Premier League appearance that so many fans had been clamouring for by Karanka or caretaker boss Steve Agnew.

Nonetheless, the department that Abad had inherited from Eric Steele and Leo Percovich was well tested. Valdes, with nearly 400 appearances for Barcelona under his belt, was adequately deputised by Guzan and Konstantopoulos. The group’s stature brought its own tests for a relatively young goalkeeper coach working in a new country and new footballing environment.

“Part of the reason Victor Orta brought me to Middlesbrough was because I believe he liked my energy, my passion, and the science and data behind the work. He loved people who could explain what they were doing and why they were doing it. But when I got to England, I realised that I couldn’t necessarily just impose my methodology on the group.

“It was really difficult. The mentality was a bit more old-school. The sessions the goalkeepers had been used to at Middlesbrough were quite traditional: volleys, shots, and dippers. There had been little connection between different elements of the game. It felt like going back ten years, from what I was used to in Spain. It was a big adjustment, and at first I felt like ‘I’m going to lose my approach and methodology’. But, you have to be smart about it.

“You’re in a new culture, and you need to adapt. You have to try and understand English people, their mentality, and how they deal with things in football. Slowly, you can begin to convince other people to trust your ideas and view of the game. It’s a process that applies to life, not just football. I realised that the barrier was my own communication, not that the goalkeepers weren’t receptive to my ideas”, Abad explains earnestly.

In the end, it wasn’t to be for the Spaniard at Middlesbrough. With the club languishing in 19th place, Karanka’s time in the North East came to an end, and with it, Abad’s first taste of English football. His short time at Middlesbrough, however, had set the foundations for a much longer test in one of English football’s most exciting recent rebuild projects.

A project that Marcos Abad could stamp his own innovation on, with significant results.

*

Age is a funny thing in football.

By the time Marcos Abad was born in the municipality of Alcoy, south-eastern Spain, in September 1985, Marcelo Bielsa had already retired from professional football in Argentina. He’d taken up a scouting position with the infamous Newell’s Old Boys, after finishing his playing career with his hometown club of Argentino de Rosario - the town also being the birthplace of Lionel Messi and Angel Di Maria.

By the time Abad took his first senior goalkeeper coaching role aged 22, Bielsa had already managed Argentina - becoming the first manager to guide a Latin American team to an Olympic gold medal (those were the days) - and was well on the way to guiding Chile to their first World Cup since 1998.

“Imagine the face on our goalkeepers when the Head Coach picked me to lead the department. I was 22. Our starting goalkeeper was 36. When I joined Elche the following year, it was Willy Caballero, who was 29 or 30 at the time. One of the best players in the entire second division. I remember a journalist commenting ‘what is Marcos Abad, 23, going to teach Willy Caballero?”, recalls Abad.

But, in his typically earnest fashion, the Spaniard stresses it was simply the first instance of an ongoing process of learning and self-development. Only a year into his time at Elche, Caballero was signed by then-La Liga side Malaga, where he’d go on to play a crucial role in their fairytale Champions League run in 2013. By 2014, he had followed Manuel Pelligrini to Manchester City.

Abad was still in Spain, and now firmly part of the furniture at Elche. He’d remain with the club for seven years in total before his move to the Premier League with Karanka at Middlesbrough. Boss-to-be Marcelo Bielsa was about to be appointed Lille manager.

Hispanic footballing culture differs from the English game in both explicit and implicit ways. Over the decades, a synthesis of the two games has produced some of the most reputed and recognisable sides in modern English footballing history. On the pitch, coaches from Spain and Latin America have developed and guided players in a way that the ‘English system’ didn’t use to cater for. The impact of these ball playing doctrines has been immense, penetrating the heart of England’s footballing institutions and radically transforming the visions of clubs up and down the pyramid.

Gone are the days of route one hoofball, big lads at the back and up front, and hardened warriors in the midfield. Some say the ‘game’s gone soft’. There is, perhaps, some truth in this sentiment. Others see the nuance and appreciate the unearthing and moulding of technical skill and tactical reformation in players who were developed in an atmosphere of a more rugged way of playing.

But these cultural differences run deeper than what we see on the pitch. Whilst mentalities around the way the game should be played have undoubtedly evolved to bring English football more in line with the styles seen on the continent, the culture of the English game still remains distinct.

“One of the things that I felt when I came here was that, in the beginning, it was more difficult to get the confidence of English players”, explains Abad.

“Us latinos, I feel we are more warm. But the dynamics are different. To me, it is normal that when you finish the set, you go to the goalkeeper and give a cuddle, give a hug. The first time I did this everyone was bemused. But it’s our way; my way. We are here, we are a unit. We are together. We can create this strength, this togetherness, with a small group, we have to care for eachother.

“The goalkeeping bond is so solid, indestructible. But you sometimes need to speak another language; the love between the group. After all, what does this work mean without love? What does this work mean without changing and transforming the human being that is in front of you?”.

Abad’s sentiment is not unsubstantiated. It’s born out of a European way of life that exists in all realms away from the footballing world. It only takes a GCSE Spanish, French, or Italian lesson to know that the common greeting in all three cultures is similar. In France, ‘la bise’ (the kiss on both cheeks). In Spain, the same. In Italy, it’s three kisses on the cheek.

But, naturally, it is different.

“I remember one sentence from Willy Caballero at Elche. When he left, he said, ‘I thought that at 30 years old I would never learn more new things. You have to open your mind’. And these words were something that I really obsessed over when I came here. Don't be invasive. But I am convinced that being more warm, expressing your emotions, cry when you miss your parents…why not! We are humans as well as footballers”.

The expressiveness of football in the Hispanic world was most definitely not lost on the man who Abad would come to work under - and where he’d continue to make a name for himself, working with one of the brightest young goalkeeping talents in the world, at the very top level.

*

Marcos Abad was only out of English football for less than a year. The Middlesbrough project had faltered and Boro would not return to the Premier League. Michael Carrick’s appointment has rejuvenated the Teeside club. Middlesbrough, at the time of writing, sit third in the Championship and on a blistering run of form that looks to be guaranteeing them a Play Off place at the very least.

The same year that Boro had been relegated to the Championship, one of football’s sleeping giants had missed out on a Play Off place after a surprising end of season fall off. Garry Monk’s Leeds United had looked certain to make the Play Offs, with striker Chris Wood scoring 30 in all competitions in the 2016/17 season, but would end up finishing seventh.

Abad joined Leeds in the summer of 2017, initially under the leadership of Thomas Christiansen. Veteran shot stopper Robert Green had departed that summer, along with Marco Silvestri, and Ross Turnbull. Felix Weidwald and Andy Lonergan arrived to form a new-look goalkeeper department that would be compounded by the rise of Bailey Peacock Farrell.

“In England, the goalkeepers have to be stronger”, notes Abad.

Indeed, Silvestri recently admitted that ‘the Championship is tough physically and technically, tactics are taken into account less. Then the league is very long, endless’. He added that ‘I got to almost 92 games, it seemed like it would never end. You arrive in February thinking you are at the end, but in reality there are still 20 games to go’.

In terms of preparing and conditioning foreign goalkeepers for the English game, Abad admitted that “it’s about how you can combine maximum power not just with maximum strength, but also with maximum speed. So it's not just structural, it's more about the motion. This is the approach we have to take”.

“Goalkeepers like Illan [Meslier] are a good example. His build - a goalkeeper that is robust but moves well - is good. In six years in English football, you are going to receive many contacts whilst catching and punching the ball”.

But Abad admits that this too was a learning curve when he joined Leeds. It was the first time in his career in England that he’d had influence over a transfer window - a process Abad continues to have a crucial role in today.

“The first year at Leeds, I made a few mistakes in terms of which kind of goalkeeper would be good here” he muses.

“It wasn’t because their performances were necessarily poor, but it was my mistake. You have to think about the game model that they’re going to face. Not every single goalkeeper, even if they are really good in their home country, can be good here. It works the same the other way round. Not all really good goalkeepers in England can be good in another country”.

Abad’s example is perhaps illustrated best by one Leeds career of recent history. Kiko Casilla’s move to Elland Road was, at face value, a successful one on the pitch. He played 36 of the 46 games that saw Leeds promoted to the Premier League as Championship champions in 2019/20, but question marks were raised about the Spanish goalkeeper’s individual performances across the two seasons he was at Leeds.

The Athletic did point to Leeds’ reported belief that Casilla had aided the development and meteoric rise of Illan Meslier. But despite his impressive footballing CV, it didn’t seem to be smooth sailing for Casilla at Elland Road. His attitude around the club was not brought into question, but it was on the pitch that fans and pundits alike sensed something of a nervousness, or a lack of the sense of settling in.

In theory, Casilla was a goalkeeper who fitted Marcelo Bielsa’s tactical regime, if not the Championship as a division. He was a unique signing - from Real Madrid - at the time, as Bielsa was almost imminently labelled upon his appointment at Elland Road in 2018.

The Argentine coach was Leeds’ managerial revolutionary, reawakening the Leeds beast and turning them into a free-flowing attacking outlet that stormed to the Championship title after an infamous defeat to Frank Lampard’s Derby County in the 2018/19 Play Off semi-final.

In the 2019/20 season, they never dropped lower in the table than fifth.

But with Bielsa came ‘Bielsaball’ and a need to condition Leeds’ goalkeepers to the methods of the influential Argentine. Ensuring the capability of his goalkeepers to play as the ‘sweeper keeper’ was one of three “really important things”, especially when Leeds brought Bielsa’s front-footed methods to the Premier League according to Abad.

“Speed is one of the key changes between Championship and Premier League. Everybody can do everything in one second less, so the method is constantly in evolution. Our style was similar but we couldn’t play exactly the same as we did the year before. So, adapting the model of the game was a constant process.

“We put in clear guidance about where we wanted our goalkeeper to be in respect to the ball. Where’s the initial position? Where will he move? What decisions can he make? Marcelo loved the high press, the energy, the aggressiveness, and creating gaps so we had to think about the different phases of play. If it breaks down and the attacker receives the ball close to the penalty box, how far and where does the goalkeeper drop to?

The second goalkeeper-related element of playing the Bielsa way was the build up.

“How can the goalkeeper be a new influence in terms of how we create different options for the team? That was the question.

“We were obsessive in trying to find the free man or find the weak side of the opponent. But after the opponent started to analyse us, then came another development, so we started to introduce more passes in spaces. Two or three players would make a move to distract the opponent and the goalkeeper would put the ball more in spaces where the spare man arrived running in. From there the key was how hard, how flat, how good is the quality of the pass?

“The next step was very important for me. We knew we were going to take risks, we knew that we were going to play around. But we had to prepare the mind. Why? Because many times we didn’t get success. That is where it was down to me to help make our goalkeepers confident to play in the way that the system required them to”, explains Abad.

“Our goalkeeper needs to know that he can resolve the problem, and continue taking risks even if we lose the ball”.

It’s fair to say that Illan Meslier is developing into exactly the sort of goalkeeper that, during our conversation, Abad alluded to trying to create. He is a case study of a young, brave, and technically and tactically able shot-stopper who fitted not only Bielsa’s demands at the time, but also the demands of physical Premier League football. As with so much of Abad’s philosophy, his success to date is one that has been aided by very human support.

“In my career, many of the opportunities I have received have been because I’ve passed through great people that let me continue growing. As a goalkeeper coach, we have to multitask. We have to be psychologists. We are managing really special people that live in something of a bubble. We are in a new generation where social media is really tough. And I have to learn how to relate to them in another way because they’re younger than me. They find things interesting that might not interest me. But I have to be empathetic, listen to them, try to know what is the problem, what is the question, and what are the things that they care about?

“But let me tell you one thing,” says Abad, as our conversation comes to an end.

“Thanks to Victor [Orta] I’m still very heavily involved with the recruitment of goalkeepers. You can sign a goalkeeper who can speak English, but it may not be their language. When you miss your parents, when you miss your friends - something that I suffered - you have to speak sometimes in their language. Sometimes it’s literally about getting an iPad with Google Translate in and you try to have the same conversation in their language.

“The most important thing is that they trust you, and not just as a goalkeeper coach. This makes the difference”.