Delving into the most existential of goalkeeping debates, we attempt to answer the question of whether goalkeeping should be analysed by-numbers or by-eye…

‘Modern technology is something that can be used to your benefit. Do I go overboard with it? No. I still think there is a human element to it. I think there is an understanding of the game that you need. But if you can use technology and numbers to your benefit then I'm all for it.’

That’s what Everton goalkeeper Asmir Begovic told Sky Sports in a feature on AFC Bournemouth’s then-trailblazing use of data in their shot-stopping department. In his time on the south coast, Begovic and his colleagues at Bournemouth had begun to use a technology called Catapult G5 under the guidance of coaching duo Neil Moss and Anthony White.

Although none of the aforementioned names remain at Bournemouth today (Begovic himself joined the Toffees in the summer of 2021, Moss left Bournemouth upon Scott Parker’s appointment as manager that same summer, and White now holds a position within the FA), the data-driven legacy Bournemouth were helping pioneer lives on elsewhere in the goalkeeping realm.

Begovic’s paradox has stood the test of time. Since the Sky Sports feature was published in December 2017, a debate has raged on surrounding the use of data in the goalkeeping community. A cold war of eye-analysis and individuality against purely quantitative analysis has been most obvious on everyone’s favourite footballing battlefield: Twitter.

Yet, away from social media, very real questions - and very real changes - are being made to the ways that clubs identify, develop, and work with professional goalkeepers.

*

“The art vs science debate in goalkeeping is a tricky one. Currently, the mainstream data available to analyse goalkeepers is not of sufficient quality to actually differentiate between a goalkeeper doing the ‘right’ thing and being unlucky, and doing the ‘wrong’ thing but getting lucky”, says Goalkeeper.com’s data scientist Dr John Harrison.

“This means it is very difficult to make any robust scientific conclusions about what goalkeepers should and should not do in certain situations. However, just because the data is not there now, it does not mean that the data will not be there in the near future and that goalkeeping will never be able to be fully treated as a science.”

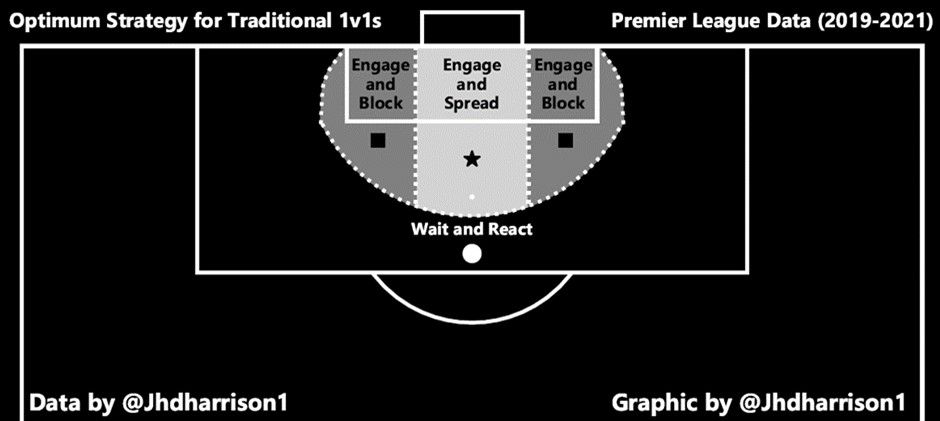

“A good example of the uses of data science in goalkeeping is my study of one-on-one situations in the Premier League over the past three seasons. By collecting and analysing data of sufficient complexity and quality, I was able to show that the technique a goalkeeper uses when attempting to save a one-on-one situation has a large effect on the probability that they will make the save”, he explains.

“To maximise their chances of making a one-on-one save, a goalkeeper should only rush out and engage the striker once they are within roughly 14 yards of the centre of goal, otherwise they should stay in their six-yard box and wait and react to the shot almost as if the situation was not a 1v1 (see graphic below).

“As the above graphic shows, different angles of attacking approach warrants different optimal actions by the goalkeeper (block, spread, or wait and react). The model proposes a solution which can now inform us as to which goalkeepers are getting ‘lucky’ and which are getting ‘unlucky’ vs one-on-ones. It also allows goalkeepers to hone in on exactly what decisions they should make in the future if they wish to concede fewer one-on-one goals on average. Here, we can highlight how scientific conclusions about the decisions and techniques goalkeepers make can be used to improve the coaching, playing, and understanding of the goalkeeping position.”

“As the data collected improves, many aspects of goalkeeping will find scientific solutions which will drive playing and coaching forwards. However, this doesn’t mean that goalkeeping will ever be 100% science and have no room for artistic interpretations. In the one-on-one study described above, the outlined solution is a set of ‘rules of thumb’ for the average Premier League goalkeeper.”

“This doesn’t reduce the value of studies like these, and this type of model is detailed to the point where it accounts for lots of different variables. However, each individual goalkeeper will have to approach one-on-ones in slightly different ways depending on their strengths and weaknesses”.

It’s arguably in this instance - the case for individuality - where the artistic side of goalkeeping comes into play. Used in the past by Premier League goalkeepers and coaches, the data Dr Harrison produces goes some way to helping refine and target training sessions, and can be adapted to the individual. Yet, although models such as Dr Harrison’s are detailed beyond the point of mainstream statistics, they are ultimately that - models and averages.

“There will likely never be a one-solution-suits-all model for goalkeeping. There will also always be room for innovation and improvisation in goalkeeping as the scientific method can only really probe what is occurring on the pitch. While we can state ‘the spread technique is more efficient for making saves than the smother technique for central, close range one-on-ones’, we cannot make conclusions about techniques that no goalkeeper has attempted to use yet”, he concludes.

“The foundations of goalkeeping will become more and more scientific as time goes on, however there will always be room for artistic innovation and personal touches in the world of goalkeeping”.

*

As Dr Harrison explains, goalkeeping data has many uses. It is prominently used in development and recruitment, but what about performance science?

Penalties are known to be statistically heavily weighted against the goalkeeper. Around 75% of penalties taken are scored, and we’ve seen goalkeepers employing all sorts of tricks to try and lower this number. From names and shot directions on the back of a water bottle, to Bruce Grobbelaar’s infamous ‘jelly legs’, closing the penalty gap hasn’t always been about luck.

Let’s go back to the distraction techniques of Grobbelaar, and many others after him. Despite the odds being firmly stacked against the goalkeeper, 2020 research suggests that ‘the goalkeeper was deemed to be a “threatening” stimulus given that this opponent ultimately stood between success and failure in the penalty kick, a suggestion that is supported by the observation that the mere presence of a goalkeeper leads to a decrease in penalty kick accuracy (Navarro, van der Kamp, Ranvaud, & Savelsbergh, 2013)’.

‘Of further relevance, the increase in attention to the goalkeeper has been shown to lead to performance decrements in both laboratory (Wilson et al., 2009) and competitive penalty kick situations (Furley, Noel, & Memmert, 2017). Subsequently, it has been demonstrated that if a goalkeeper attempts to distract a penalty taker by waving their arms, for instance, this has the potential to further orient the penalty taker’s attention towards them and thereby impair performance (Wood & Wilson, 2010)’.

So, when it comes to penalties, we see the art and science of distraction in play. ‘Art’ in the sense that a goalkeeper’s preferred technique is often unique and sometimes iconic, but ‘science’ in the subconscious reaction it causes. Let’s put it this way: when you next see a goalkeeper bad-mouthing the striker before a penalty, it’s probably not likely that they’re fully aware of the impact they’re having.

It’s more likely that the distraction is a habit, or a way of self-calming. There is undoubtedly science behind it, but would the average onlooker or indeed goalkeeper themselves realise that? It’s this exact problem that makes the art vs science debate so contentious in goalkeeping. We live in buildings, and see them every day. We can judge a nice building from a dilapidated one. There is, in its nature, the science of architecture behind that design, but the building itself is still a ‘work of art’.

Furthermore, some will go as far to use scientific principles to justify goalkeeping’s individuality. They claim that this science makes goalkeeping an art, because goalkeeping physiology is ultimately a natural thing. But that in itself is impossible to an extent; the rebuttal of ‘textbook’ techniques and data that argues for it because goalkeeping isn’t an exact, machined science, but the use of science to justify the opposite theory.

*

Again, we revisit what a goalkeeper does consciously and subconsciously. Similarly, there’s a difference between what we see as the holistic picture of a goalkeeper, and isolating individual actions.

Goalkeeping can be an art, underpinned by science. Sport in general is an entertaining spectacle, but let’s view things differently. If you go to the West End to watch a musical then, of course, there is literal biological science in the voice ranges of the performers. But the West End isn’t a science. It’s an art - a craft - dedicated to perfecting through years of emotional investment and holistic skill development.

The goalkeeper also puts on a show. Goalkeepers are mavericks, and do things differently from the rest of the positions. Sometimes, there is no straight logic or method to what a goalkeeper does, rather rushes of adrenaline (yes, this is technically scientific but overarchingly intrinsic) and second-splitting reactions to stimuli moving at up to 80mph. You could argue that these skills are not thought out and systematic but naturally exist within the chosen few with goalkeeping genes.

Hence, when we look at goalkeeping and the science vs art debate, we should be careful to distinguish between reactive analysis and understanding what happens in the split second a save is made.

To perform in the manner a goalkeeper does holistically - balancing strenuous mental dedication, intrinsic skill, and ultimately a conscious desire to - proverbially - put your head where it hurts. Being willing to put yourself in positions unnatural to the human body, be innovative in how to do so, and ultimately enjoy the thrill of playing the most controversial ‘character’ in a game based on what you aim to prevent, is creative in many ways.

It’s this thrill that removes the cold science from goalkeeping, even though the existence of data and science within goalkeeping is inevitable. To be a goalkeeper is not a thought-out experiment, but almost a calling that only a special few will hear and answer. The role is almost mythical - hiding secrets that only those who have experienced it will be able to discover and understand - whilst bringing a sense of the impossible to football.

NASA may work on defying gravity, but whether they do it with style is another matter. Besides, it would be pretty tough to monetise watching a scientist model astrophysics every single Saturday afternoon for two hours.

When it comes to individuality, goalkeepers are consciously creative. Each shot-stopper has their own style to an extent, and certain USP’s that they champion, forming an identity. With Jens Lehman, it was personality. With Manuel Neuer, it’s the sweeper-keeper approach. With Ederson, it’s the eleventh man. With Lev Yashin, it was incredible efficiency and breathtaking elegance in technique.

There has been an intention, in all of these cases, to bring something different essentially by being themselves. Besides, when innovation occurs, is there not a degree of art involved?

When somebody does a scientific experiment, they tend to look for an objective, defined result (one number). In theory, the principle of science is that it can’t really be argued with. This isn’t always true, however, and in goalkeeping we see why.

In creating an experiment, scientists are being objective to an extent. Often, they will be looking for a result that favours their hypothesis, and want to find the method that proves it or gets the desired result. However, in doing this, they are being subjective. When something is innovated in goalkeeping, such as the spread technique or side volley, art is ‘happening’. We then look to ‘reactive’ science to develop and refine it.

Each of these goalkeepers consciously forged an identity, reacting to the demands of the age and putting their own unique twist on goalkeeping as a position. There is beauty in the approach of the goalkeeper to a sport that is becoming ever-more scientific, pushing the boundaries of what the human body can withstand and, in tandem, creating the world’s most intriguing display of human physical capability, week in, week out.

To be a goalkeeper is to be subjective.

*

But science is goalkeeping isn’t just hypothetical. It can make a real impact, on real teams and goalkeepers.

One such team was Parma Calcio, in Italy’s Serie B. With the goalkeeping department under the guise of Swede Maths Elfvendal until early July 2022, the likes of Gianluigi Buffon have been using data to refine performance at an elite level. But how did Elfvendal, also the Swedish National Team goalkeeper coach and now Head of Goalkeeping and Set Pieces at StatsBomb, go about using science and data in his practices?

“Your elbow. My AirPods. This chair. These things are all science, and everything is technically a science when you trace it backwards”, begins Elfvendal.

“I could make a joke now and say that it’s 87% science, or 87% art. But ultimately goalkeeping is not black and white. I think data can help you to just think about football. You might wonder, ‘okay, the data shows me this. Why? What is it saying about the goalkeepers?’. But the very important lesson here is that you work with people. And no one person is exactly the same as another. I might come across ten or eleven different goalkeepers, and I cannot have exactly the same approach to everyone”.

“I tend to use data to understand what we can add to our overall philosophy”, he continues.

“It's really helped me to take a new perspective on goalkeeping. Sometimes I use data to plan and enhance our goalkeepers’ sessions, to make it a little bit more complex and challenging.. One v one situations is a good example here; we read the situations and signals we find in the game that helps us to find the perfect position a little earlier. But I believe you need to mix science and art together - and that’s the fun part!”.

“We didn't used to be able to access an empirical view of goalkeeping. Now, we have the chance to gain knowledge from so many different areas - and I'm excited to be part of this generation of coaches”, he states.

Whether a stricter approach than Elfvendal outlines to using data in goalkeeping development is for better or for worse, is up for debate. For years, academy goalkeepers have continuously been judged against strict growth and development criterias. There are countless stories of goalkeepers going under the radar or being released on the basis of their height, often at particularly young ages.

There is a discussion that should be had within the goalkeeping world as to what data clubs begin using when recruiting goalkeepers. In the same way that a clean sheet cannot define a goalkeeper’s performance, their height should not define their prospects of progressing through the game providing it can be compensated for.

Perhaps a different discussion should be being had. Many argue that science is objective (in goalkeeping, you can’t really argue with advanced statistical modelling) but science is never entirely objective. ‘Experiments’ are undertaken by methods that are consciously designed to create a certain outcome. How does this translate to goalkeeping?

Well, if the method is changed - i.e. the attitude towards what the contemporary model professional goalkeeper looks like - then types of data used to evaluate goalkeepers should also change. Sadly, this isn’t the case in the academy environment where there arguably remains a gulf between the requirements of an academy goalkeeper and a first team one.

As seen with the fascinating story of former AFC Wimbledon goalkeeper Zaki Oualah, science doesn’t always supersede talent. Oualah, 26, won his first professional deal at the League One side at only 5”9.

Regardless, goalkeeping needs to be open enough to blur the boundaries between art and science. As with most things in the sporting arena, the best outcomes come through a mix of planned magic and the unexpected. Goalkeeping is no different. Whether the position is reduced to numbers de facto in the years to come is yet to be seen. Yet, there’s an element of unpredictability that underpins the beauty of goalkeeping that will always exist in heroic actions of those who brave life between the posts.