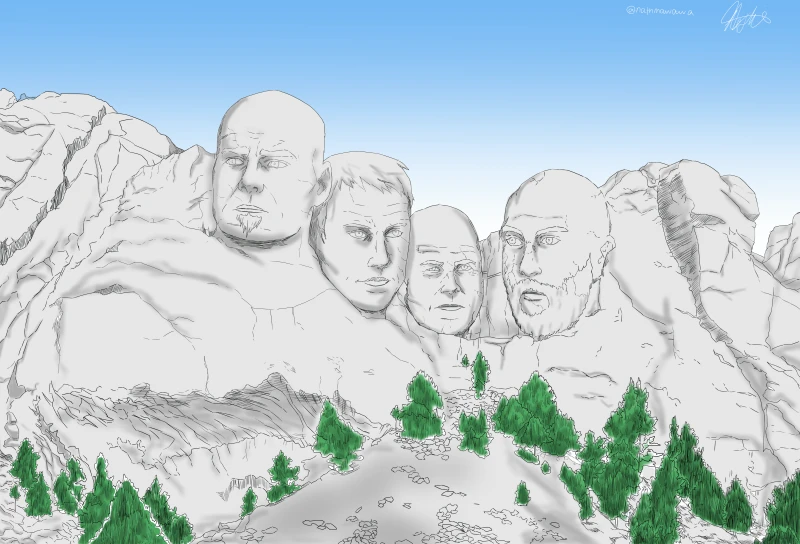

Keller. Friedel. Howard. Steffen. The invisible footballing transatlantic partnership between England and the States has proved fruitful in between the sticks…

There are three similarities that exist between the former President of the United States, Donald Trump, and goalkeepers.

The first is a maverick (and on occasion dangerous) approach to work. Trump’s path to power shook the very foundations of American politics; the way he undertook his role in office was unorthodox to say the least. It’s these two intriguing traits that can also often be embodied by the goalkeeper, although not causing such societal fracture.

Secondly, following his controversial presidential campaign in 2016/2017, there is another adjective that could apply to both Trump and goalkeepers: brazen. The 75-year-old’s populist brand of Republicanism was defined by outlandish ambitions and outrageous claims, leading to his banning from Twitter in January 2021. Much like goalkeepers on the football pitch, Trump had a confidence that didn't always serve him well.

The third and final similarity between goalkeepers and Donald Trump is that, high on their list of priority, was defence. The Trump administration's 2019 $738 billion defence bill was a testament to this, with the ex-President increasing defence spending each year he was in office.

Historically, America been seen as a ‘defender’ of freedom. Throughout its history, most of the conflicts it has been involved in have been fought abroad. In fact, the last battle fought on American mainland soil against a foreign power was actually against Britain themselves, in the War of 1812.

Over the course of history, Britain and the USA have intertwined in a plethora of areas - including in matters of defence in the past. But when it comes to defence, there is another area in which Americans have defended particularly well: in football (or soccer) - specifically, in goal.

*

“They love a goalkeeper in the States, you know. The last line of defence, the hero making saves…we definitely get a lot of a lot more press out here. In England, people can't wait to batter a goalkeeper. If you make an unbelievable save, it’s a save you should make. If it goes in, you should have saved it. From my experience in the MLS, attitudes towards goalkeepers are completely different”.

That’s Englishman Jonathan Bond’s view on the sentiment surrounding goalkeeping in the USA. Currently LA Galaxy’s number one, Bond’s delight in his decision to make the move across the world to join the Galaxy is palpable - even through Zoom.

From an English perspective, ‘goalkeeping’ and ‘American’ are synonymous in the sporting arena. It’s this infectious shot-stopping bug that seemed to infect plenty before Bond’s time in the States, and will hopefully continue to do so for years to come.

But those nouns aren’t only synonymous within the USA. In England, some may argue that the stereotype of American goalkeepers who played in England is one of reliability, solidity, and ‘safe hands’. Cult heroes such as Friedel himself and Kasey Keller epitomise this image of the American ‘walls’ that shut out Premier League attackers over 20-plus years in England.

Keller himself played 201 Premier League games, recording a 73.9%* save percentage over his eight seasons across spells at Leicester, Tottenham Hotspur, Southampton and Fulham. Friedel, meanwhile, played over twice as many games (450 to be exact), maintaining an equally impressive overall save percentage of 76.4%**.

Fridel’s large personality and even larger frame (6’3 lengthways by all accounts), along with his longevous career between the sticks, gave him an ‘Uncle Brad’ vibe. He was the goalkeeping definition of ‘evergreen’; a tough Midwesterner who defied the odds (and in some ways the British courts, finally moving to Liverpool after four rejected work permits). To this day, Friedel holds the Premier League record for the most consecutive starts, numbering 310 between 2004 and 2012.

Tim Howard infused the Premier League with an Athleticism that defied his age. Joining Manchester United from the preceding brand of the New York Red Bulls, MetroStar, the ex-Everton legend was a mainstay between the posts at Goodison Park - bald-headed and groomed-bearded throughout - becoming an icon of American football in England.

The ‘original’ Anglo-American goalkeeping trio have all spoken in the past about how coming to play in England shaped their careers as goalkeepers. Speaking to Manchester United, Howard described joining the Red Devils as ‘sink or swim’, explaining ‘those early shooting practises at the end of training were an education. I couldn’t even see the ball half the time, never mind keep it out of the goal, and when I did get my hand to the ball it would hurt, so that made me realise how high the standard was and how much I’d have to improve. Quickly’.

It’s noted that, for boyhood Liverpool fan Friedel, moving to England was in part a dream come true. The line he toed when speaking to the Coaches Voice was essentially a development of Howard’s own memoirs. ‘It was up to us to prove people wrong’, he said in reference to the reputation of American footballers - and especially goalkeepers - in England.

‘That wasn’t easy. There was a feeling that you had to perform twice as good as you ever had before in your career to get the jobs in Europe…or you wouldn’t be given the time of day’.

The words of Kasey Keller, in conversation with The Athletic, were almost a carbon copy of Friedel’s. In my first year in England, the majority of interviews I gave were preceded by, ‘What is an American doing playing here?’ And second, ‘What is an American doing here playing so well?’’, he detailed.

It’s interesting that some of the most iconic pairs of ‘safe hands’ in Premier League history were indeed Americans who had to become accustomed to defying the odds from arrival - and more cases than they would care to count, pre-arrival. Work Permit difficulties struck Keller, Howard and Friedel on multiple occasions and threatened to end their English careers before they’d begun. Between Howard and Friedel, the matter of the work permit was particularly contentious.

On the pitch, the American stereotype was a problem. It’s arguable that English fans are more conservative than many would wish to admit - or perhaps recognise - when it comes to fan culture. This isn’t negative; English football is steeped in history and rooted in tradition. After all, the beautiful game as we know it was invented in England. Clubs and fans contend relationships that have spanned over generations.

Perhaps it is for this reason (ironically) that American goalkeepers have tended to be successful in England, especially in the core years that the likes of Keller, Friedel and Howard played here. When we consider the reason why American ‘soccer’ has been negatively stereotyped - even to the point of ridicule - in the past, the achievements of these goalkeepers and indeed their affinity and popularity with fans and clubs isn’t quite so mysterious. In turn, the stereotypes become…just incorrect.

*

But what was this stereotype surrounding American goalkeepers when they first began to cross the Atlantic?

In a 2007 article by the Guardian, the late columnist Steven Wells attributed the Brits’ distaste for American football as more of a fear of the US beginning to become ‘soccer-savvy’, as he deemed. American football was new, and ‘new’ and ‘football’ were words that, for decades, were not necessarily synonymous with the English game. Innovation - in goalkeeping and more generally - tended to come from Europe or South America, with the Three Lions suffering at the hands of more innovative footballing cultures one too many times.

Catching up was tricky; the Premier League only introduced the Elite Development Performance Plan in 2011 in an attempt to bring English football development on-par with other countries. It was in this new environment that the new, ball-playing English goalkeeper began to be developed, such as Jordan Pickford who was 16 when the new programme was introduced.

In this sense, the new American goalkeeper - and football culture - arguably suffered primarily for the fact that it was new. New meant a threat to an ‘English institution’, and a natural suspicion of the potential of the American player.

‘Soccer’ was arguably also viewed with suspicion by English fans due to its immediate commercialisation. The image of American sports and the perhaps entertainment-first attitude they adopt (cue images of Cheerleaders at Basketball games, the Superbowl half-time performance and its franchise model, and the organ theme tune of the baseball) was perhaps naturally at odds with the ‘tougher’ English game. This attitude was also applied to the American goalkeeper.

Yet, Brits were arguably focusing on the wrong side of American sports. The American goalkeepers who have been in the Premier League arguably were so because they were actually much more English than one expected them to be. Brad Friedel’s physique and ‘line-goalkeeping’ instincts were stereotypically English traits, and the former inevitably aided his adjustment to English football in a way that has presented problems for other foreign goalkeepers coming to England, such as David de Gea or Kepa Arrizabalaga more recently.

In Kasey Keller, we can see some of Peter Shilton. An efficient goalkeeper with the ability to pull off the spectacular, Keller shared Shilton stylistically in his penalty area presence and efficient style. Calming and secure, the American and Shilton were truly reliable shot-stoppers. Holistically, they were goalkeepers whose career longevity and consistency mirrored their respective abilities: great.

One name that always comes to mind with reference to Howard’s style is Gordon Banks. Banks’ consistency and unrivalled athletics were two virtues that Howard embodied. Stylistically, however, there are certain uncanny similarities in the two goalkeepers’ play. Both particularly natural goalkeepers, whose excellent spring and gangly arms were an eclectic mix, ‘Howard the American’ was not such a rarity to the English game in style. The stereotype was superficial.

Howard never quite got the rub of the green at United, nor Friedel at Liverpool. Did the American stereotype come into play? If we’re talking stereotypes, perhaps it is rather stereotypical American optimism that the aforementioned three goalkeepers embraced after droppings, rejections, education-by-fire, and more.

Lifelong participation in hand-eye coordination based sports, in a large part, arguably formed the backbone of American goalkeeping skill, but immersion in contact sports such as American football (which Keller played until he was 16) was another potential reason for the battle-hardiness of the USA’s shot-stopping crop. None of the American goalkeepers who played in England were physically ‘soft’, each adapting quickly to the hard-hitting nature of English football at the time.

Take Reading legend Marcus Hahnemann, for example. Bald, obviously, and sporting an iconic goatee, Hahnemann was a Yank in the UK through and through. A huge American Football fan, playing it in his youth and, in retirement, notably taking up an eclectic mix of hunting, fishing and skiing, Hahnemann’s personality was larger than life. The self-professed metalhead’s exit from Wolves - for whom he signed from Reading in 2009 - was as hilarious as it was unsurprising. Not one to hold back - and not one to mince his words, Hahnemann described his last game for Wolves in comical detail to BerkshireLive in 2020.

‘George Elokobi was a big buddy of mine and he was blamed for us losing that game because he ended up making a tackle on the end line – he got the ball completely and never touched the guy – but they got a free-kick and [Robert] Huth scored a header.

‘Terry [Mick McCarthy’s assistant Terry O’Connor was talking to Elokobi and I was like, ‘Terry, it wasn’t even a foul, he got the ball fairly’ and he just told me, ‘I’m not talking to you, when I want your opinion, I’ll give it to you.’ Well, imagine how well that went.

‘The next thing I know, I’m in the shower, naked, I’ve got soap all over me, and Matt Murray – in a suit – is trying to hold me back because Terry’s still having a go at me and I’m going to kill him. Matt guarded me and wouldn’t let me go for about 20 minutes while I cooled off!’.

Tough is most likely another more pertinent stereotype to apply to American Premier League goalkeepers past.

*

Not only did American goalkeepers in England have to work against the ‘soccer stereotype’, but their routes into the Premier League were mired with legal difficulties. As mentioned, work permit issues mired the arrival of Brad Friedel and Tim Howard in the Premier League. The contentious issue also led to a feud between the pair, beginning in 2014, after Howard accused Friedel of attempting to sabotage his application for a work permit at Manchester United.

The two goalkeepers reportedly made peace later that year, but are both prime examples of the difficulties that can face international players generally. As a result of Brexit, the permit application rules for foreign players entering the UK changed. Players moving directly to the UK have to fulfil certain conditions.

From January 2021, all employment related immigration claims to the UK are considered equally within football in terms of the citizenship of the applicant. In other words, Americans are treated no differently from Germans, Czechs, Russians or Japanese players. Permit applications (and their chances of success) work on a point based system.

For a player to apply for a UK work visa, they must receive a Certificate of Sponsorship. To earn this, a player must first receive a Governing Body Endorsement - a GBE. The awarding of a GBE is based on different criteria:

- The applicant club must be in membership of the Premier League or Football League. During the period of endorsement, the player may only play for clubs in membership of those leagues (i.e. the player may not be loaned to a club below the Football League);

- The player must have participated in at least 75% of his home country’s senior competitive international matches where he was available for selection during the two years preceding the date of the application; and

- The player’s National Association must be at or above 70th place in the official FIFA World Rankings when averaged over the two years preceding the date of the application.

Players must reach 15 points to automatically qualify for a GBE. This can be achieved by meeting all of the above three criteria. However, there are other opportunities for players to gain points, from youth international competitions to the quality of the selling club.

The two American goalkeepers currently registered in the 92 professional English clubs are Ethan Horvarth, at Nottingham Forest, and Zack Steffen at Manchester City. Unlike their American predecessors, the pair’s work permit applications seemed to pass without difficulty. However, only Steffen was actually signed directly from an American club. Horvarth signed from Belgian side Club Brugge.

Steffen and Horvarth are yet to reach the levels of Friedel, Howard and Keller. It’s only natural - the duo have only made so many appearances in the Premier League and Championship respectively. It’s true that when the American Premier League goalkeeper is mentioned, the aforementioned three are the names that come to mind, but there have been several other successful goalkeepers who have made the trans-Atlantic goalkeeping trip.

The first American goalkeeper to sign for a Premier League team was Ian Feuer of West Ham United in 1994.. Three years earlier, Jurgen Sommer had become the first US shot-stopper to sign for a first division side (Luton Town). Sommer actually signed for Queens Park Rangers in 1995 - the summer after Feuer moved to West Ham - but the latter never actually made an appearance for the Hammers.

As such, Sommer was the first American goalkeeper to ever actually play in the Premier League.

After Feuer and Sommer, in the sub-generation of Friedel, Howard and Keller, came Hahnemann as mentioned. Brad Guzan was another. Also bald (it’s not a surprise by this point), he looked like a slightly scarier version of Brad Friedel but was an equally capable goalkeeper who arguably hasn’t ever received the credit he deserves.

Whether that is understandable or not is a different story.

144 appearances for Aston Villa put Guzan into the Premier League spotlight. Yet, despite missing only six league games between 2012 and 2015, Guzan trashed his relationship with the Villa Park faithful as his and the club’s form drastically declined. A row with fans from the bench in an FA Cup tie away at Wycombe epitomised the breakdown in relationship, with Villa fans seldom disappointed to see him depart for Middlesbrough in 2016.

Guzan marked the last of the core of American goalkeepers who claimed number one spots across the Premier League in the 2000s. His game time at Middlesbrough was limited, and he departed for home in 2017, joining Atlanta United. Since Guzan’s departure for America, Horvath and Steffen have been the two American goalkeepers in the top four flights of English football but neither have found regular game time.

Matt Turner’s move from the New England Revolution to Arsenal will go through in the summer of 2022. His arrival at the Gunners will add another Yank to the Premier League list, but whether he will start ahead of Aaron Ramsdale is unlikely.

As such, we could remain waiting for the next generation of American goalkeepers to influence Premier League football. And, if patience means that the next batch are of the calibre of their predecessors, then it will be worth the wait.